Pancreatic cancer is one of the deadliest types of cancers in humans. It is the fourth leading cause of cancer-related deaths in the western world. The early stages of the disease often progress without symptoms, so diagnosis is usually very late. Another problem is advanced tumors—and their metastases—can no longer be completely removed. Chemotherapies, in turn, attack not only the tumor cells but also healthy cells throughout the body.

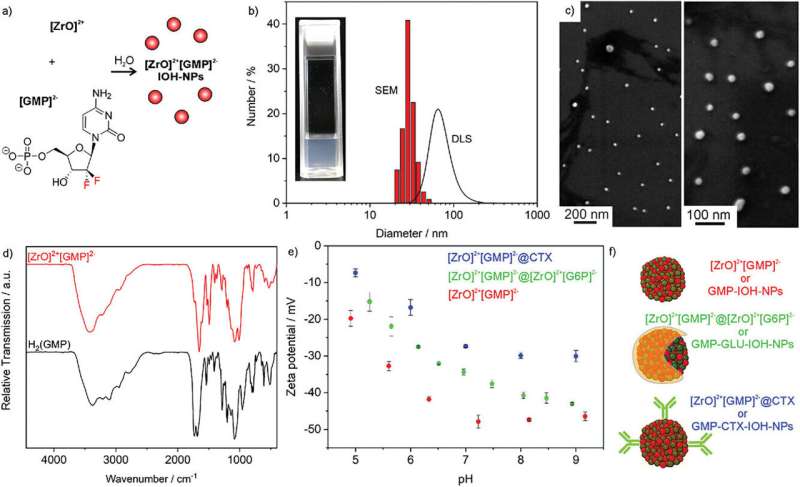

Innovative nanoparticles could be a new approach to treat cancer more precisely. This approach was developed by a research team from the Max Planck Institute (MPI) for Multidisciplinary Sciences, the University Medical Center Göttingen (UMG), and the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT). The therapy is now to be optimized for clinical application as quickly as possible.

The method promises to treat pancreatic carcinomas with more accuracy and with fewer side effects than current cancer therapies. Using nanoparticles, the active substance Gemcitabine was transported in large quantities directly into the tumor.

“Targeting the drug in high concentrations into the tumor cells with the help of the nanoparticles increases the efficacy and spares healthy cells. This can reduce the severe side effects that occur with Gemcitabine,” explains Myrto Ischyropoulou, lead author of the study recently published in the journal Advanced Materials.

“Currently, patients are given the free drug. This is distributed throughout the body and can lead to toxic effects in all parts of the body. The nanoparticles, on the other hand, release the drug mainly in the tumor.”

Joanna Napp, scientist at the UMG and the MPI, adds, “Using imaging methods, we have already been able to demonstrate in mouse models that the nanoparticles accumulate in the tumors.”

The administration of nanoparticles also allows resistance mechanisms in the tumor to be circumvented. “Free Gemcitabine is often no longer taken up by the tumor very early on and is thus largely ineffective there. However, it still leads to considerable side effects, for example in the liver and kidneys,” explains Claus Feldmann from KIT. “By using a different uptake mechanism in tumor cells, our nanoparticles could be a very effective new therapeutic approach here.”

The research success is an excellent example of successful interdisciplinary cooperation, says Frauke Alves, group leader at the MPI and the UMG. “From the idea to the development of the new nanoparticles to preclinical testing, chemists, biologists, pharmacists, and physicians have worked hand in hand.”

With a spin-off, the scientists are now working to bring their new nanoparticles out of the test phase and into clinical use as quickly as possible.