Self-propelled nanoparticles could potentially advance drug delivery and lab-on-a-chip systems—but they are prone to go rogue with random, directionless movements. Now, an international team of researchers has developed an approach to rein in the synthetic particles.

Led by Igor Aronson, the Dorothy Foehr Huck and J. Lloyd Huck Chair Professor of Biomedical Engineering, Chemistry and Mathematics at Penn State, the team redesigned the nanoparticles into a propeller shape to better control their movements and increase their functionality. They published their results in the journal Small.

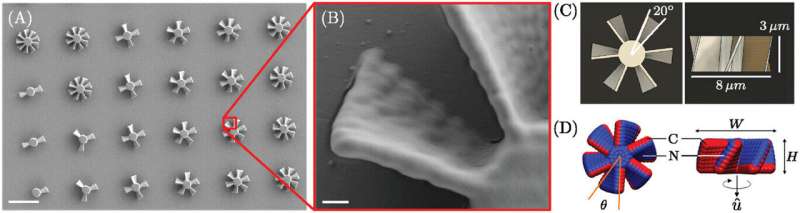

Due to fabrication challenges, the shape of nanoparticles has previously been limited to rods and donuts, according to Ashlee McGovern, doctoral student in chemistry at Penn State and first author on the paper. With a nanoscribe machine that can 3D print at the nanoscale in Penn State’s Materials Research Institute, McGovern experimented to optimize the nanoparticle shape. She redesigned the shape of the particles to a propeller, which can spin efficiently when triggered by a chemical reaction or magnetic field.

The propeller shape employs chirality, akin to a screw or spiral staircase, where the top face is mirrored by the bottom face.

“Shape predetermines how a particle is going to move,” McGovern said. “Chirality, or handedness, as a design feature has not been utilized enough in nanoparticle research and is a way to make the particles move in more and more complex ways.”

The chiral shape allows the particles to move in a prescribed direction, and, depending on the tilt of the blades, spin clockwise or counterclockwise in place, fueled by a chemical reaction between the metals in the nanoparticles and hydrogen peroxide.

After experimenting with different numbers and angles of fins, as well as different thicknesses, researchers found that using four or more fins at a 20-degree tilt and 3.3-micron thickness allowed for the greatest amount of stability. With three or fewer fins, the propellers exhibit uncontrolled movement.

The increased control allowed researchers to manipulate the particles to capture and transport polymer cargo particles.

“Using a magnetic field, we can steer the micropropellers to hunt down and collect cargo particles,” McGovern said. “Our lab’s rod- and donut-shaped nanoparticles would accidentally pick up cargo, but not in any controlled fashion.”

To further control the movements of the particles, researchers manipulated the rotational direction of the micropropellers.

“With the built-in flows that the particles create, we can control the particle-to-particle interactions between the two propellers,” McGovern said. “Switching the rotational direction from counterclockwise to clockwise and vice versa allows two propellers to attract or repel each other.”

Aronson, who heads the Active Biomaterials Lab in which McGovern works, emphasized the future reach of this research.

“Using tailored mechanical, magnetic and chemical responses, we can exert more control than ever before on these nanoparticles,” Aronson said. “In the future, we can leverage this control to apply this technology to design concepts for microscale devices or microrobotics.”