A University of Houston researcher is reporting a new method to detect cancer which could make cancer detection as simple as taking a blood test. With a 98.7% accuracy rate, the method—which combines PANORAMA imaging with fluorescent imaging—has the potential to detect cancer at the earliest stage and improve treatment efficacy.

The remarkably precise method allows researchers to peer into nanometer-sized membrane sacs, called extracellular vesicles or EVs, that can carry different types of cargos, like proteins, nucleic acids and metabolites, in the bloodstream.

When Wei-Chuan Shih, Cullen College of Engineering professor of electrical and computer engineering, and his team examined the number and cargo of small EVs inside patients with cancer and those without. The paper is published in the journal Communications Medicine.

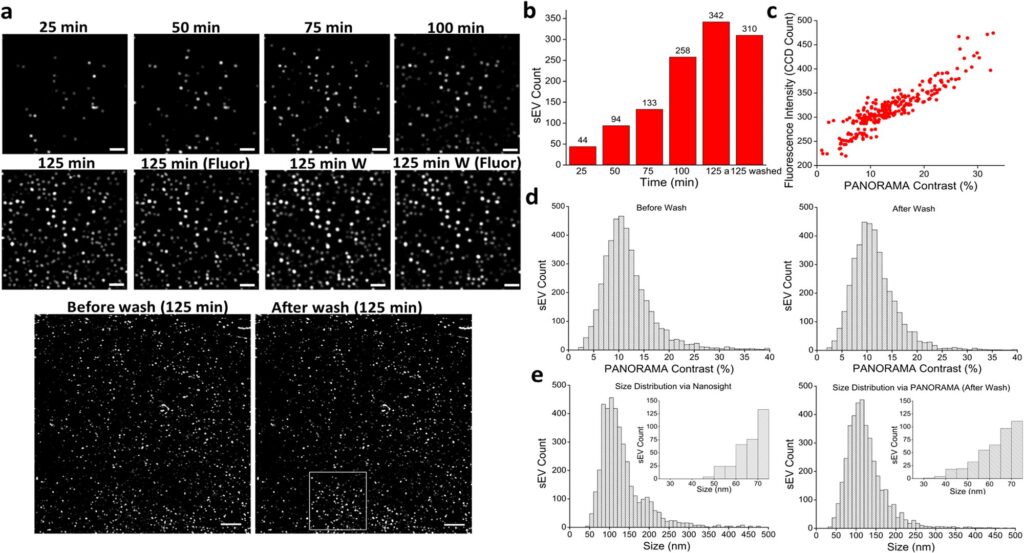

“We observed differences in small EV numbers and cargo in samples taken from healthy people versus people with cancer and are able to differentiate these two populations based on our analysis of the small EVs,” reports Shih. “The findings came from combining two imaging methods—our previously developed method PANORAMA and imaging of fluorescence emitted by small EVs—to visualize and count small EVs, determine their size and analyze their cargo.”

In 2020, Shih debuted the PANAROMA optical imaging technology, which uses a glass side covered with gold nano disks that allows users to monitor changes in the transmission of light and determine the characteristics of nanoparticles as small as 25 nanometers in diameter. PANORAMA takes its name from Plasmonic Nano-aperture Label-free Imaging (PlAsmonic NanO-apeRture lAbel-free iMAging), signifying the key characteristics of the technology.

For this research, supported by the National Institutes of Health, it was a matter of counting the number of small EVs to detect cancer.

“Using a cutoff of 70 normalized small EV counts, all cancer samples from 205 patients were above this threshold except for one sample, and for healthy samples, from 106 healthy individuals, all but three were above this cutoff, giving a cancer detection sensitivity of 99.5% and specificity of 97.3%,” said Shih.

To further test the performance of the detection threshold of 70 normalized small EV counts in plasma, the team analyzed two independent sets of samples from stage I-IV or recurrent leiomyosarcoma/gastrointestinal stromal tumors and early-and-late-stage cholangiocarcinoma that were anonymously labeled and mixed in with healthy samples and achieved 100% accuracy.

“With further optimization, our approach may be a useful tool for cancer detection screening in particular and provide insights into the biology of cancer and small EVs,” said Shih.