Researchers from the University of Waterloo have developed a new technology that can hold an entire course of antibiotics in one tiny dose and deliver on demand just the right amount of medication that a particular patient needs to fight an infection.

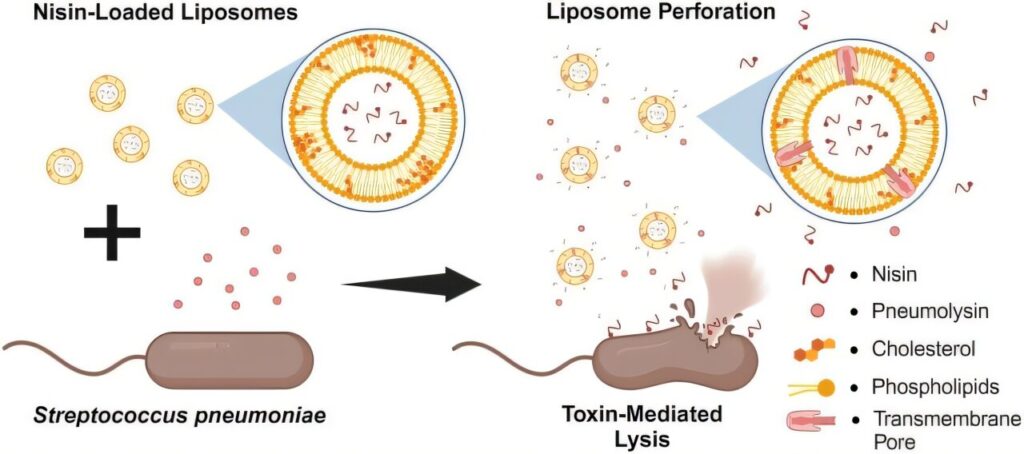

This breakthrough in targeted medicine is the result of two new studies that tested this drug-delivery system on two bacterial strains that negatively affect millions of people worldwide. Streptococcus pneumoniae causes meningitis, sepsis and bacterial pneumonia, potentially fatal conditions. Gardnerella vaginalis is mainly associated with bacterial vaginosis, causing discomfort and pain.

The two studies, “Bacteria-responsive drug release platform for the local treatment of bacterial vaginosis” and “Pneumolysin-responsive liposomal platform for selective treatment of Streptococcus pneumoniae,” were published in Nanotechnology and Drug Delivery and Translational Research, respectively.

The team from the School of Pharmacy at Waterloo found that this personalized nanomedicine, which attacks bacteria at the molecular level, results in patients taking the exact amount required to fight the infection while reducing the risk of antibiotic resistance. With the misuse and overuse of antibiotics, bacteria strains develop a tolerance, resulting in antimicrobial resistance (AMR), a global threat.

“Ideally, the patient takes the full course of antibiotics at once, and so patients don’t need to worry about forgetting to take a pill or only taking it with food,” said Dr. Emmanuel Ho, lead researcher and a professor at Waterloo’s School of Pharmacy. “You know the nanomedicine is working is working when disease symptoms improve.”

This new technology consists of fatty compounds invisible to the eye that are tailored to only release a drug in the presence of toxins produced by specific types of bacteria.

“Compared to traditional therapies that release drugs continuously, even when not needed, our nanomedicine is designed to release drugs only when required, which will potentially reduce severe side effects associated with excess dosing,” Ho said.

“In addition to combating AMR by ensuring patients take all of their medicine, there would be fewer side effects because they also don’t take too much of the drug. Our technology is far-reaching, and this is just the beginning.”

The nanomedicine that the body does not release will break apart organically in the body without side effects. This feature ensures the patient doesn’t take too much medication and the body is not constantly exposed to the drug.

There is a high rate of reinfection when treating Gardnerella vaginalis and Streptococcus pneumoniae with antibiotics. The aim was to develop a drug where a patient doesn’t have to keep taking multiple doses to prevent reinfection. Ho’s goal is to use this technology in the prevention and treatment of many diseases.

The team plans to commercialize this nanomedicine. In addition to medical applications, this technology is currently being tested for use in packaging to increase the shelf life of food. Applying this technology to the packaging of processed meat, where the container touches the food directly, would keep food fresher longer. According to the United Nations, a billion tons of food was wasted globally in 2022.