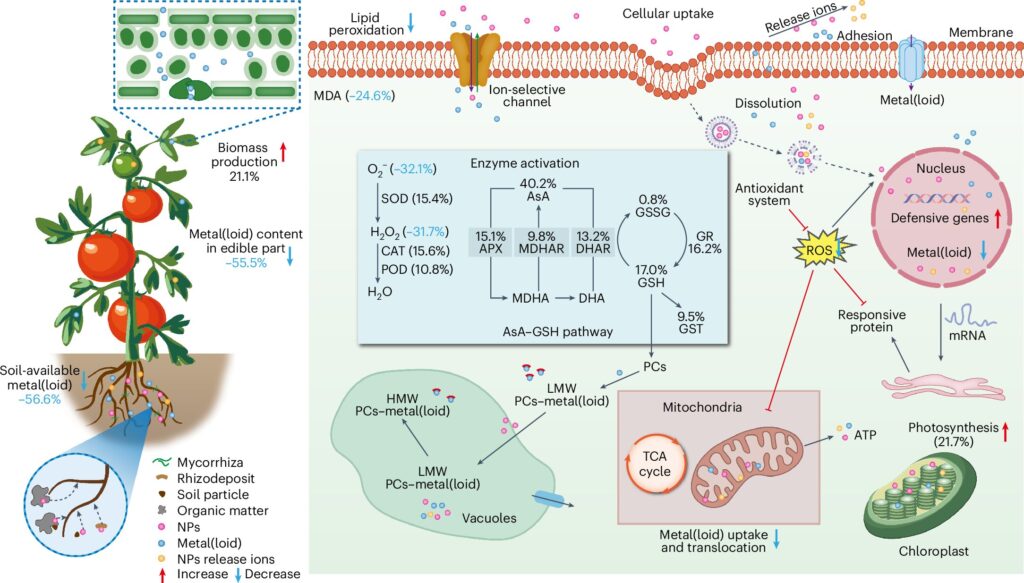

One of the pressing problems that the world faces in the era of climate change is how to grow enough healthy food to meet the increasing global population, even as soil contamination rises. Research recently published in Nature Food by an international team of scientists led by the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Guangdong University of Technology, and Central South University of Forestry and Technology, has shown that nutrients on the nanometer scale can not only blunt some of the worst effects of heavy metal and metalloid contamination, but increase crop yields and nutrient content.

“Much of the world’s arable soil is contaminated by heavy metals, like cadmium, lead and mercury, as well as metalloids, like arsenic and selenium,” says Baoshan Xing, University Distinguished Professor and director of the Stockbridge School of Agriculture at UMass Amherst.

Xing, who is also the paper’s senior author, notes that such contamination puts severe stress on the ability to grow staple crops, which also affects the nutritional value of the crops that manage to survive.

“We need to come up with solutions to reduce the heavy metals that wind up in our food,” says Xing, and one approach that has shown promise is the use of nutrients at nanoscale, or what he calls a “nano-enabled” agriculture.

The bulk fertilizers that you may be more familiar with are made up of large particles, which aren’t as readily absorbed by the crop. This means that farmers need to apply more, which then increases the levels of fertilizer runoff into streams, lakes and the ocean. However, crop nutrients at the nanometer scale can be specifically designed and mixed for particular crops, growing conditions and application methods, and engineered so that the target plant can most efficiently absorb the nutrients into its system, cutting down on the amount of fertilizer needed, keeping costs down and limiting runoff.

Though nanomaterials are already available on the agricultural market and have plenty of peer-reviewed science looking at their effect on the soil and crop growth, the research by Xing and his colleagues is the first comprehensive account of the effectiveness of nanomaterials as a class, with results that offer practical insights to help steer sustainable agriculture and global food safety.

“We collected data from 170 previous publications on the effectiveness of nanoparticles in reducing heavy metal and metalloid uptake,” says Chuanxin Ma, the paper’s co-lead author, who completed his doctoral training at UMass Amherst’s Stockbridge School of Agriculture and is now a professor at China’s Guangdong University of Technology. “From those 170 papers, we collected 8,585 experimental observations of how plants respond to nanomaterials.”

The team then conducted a meta-analysis on this enormous trove of data, running it through a series of machine-learning models to quantify the effect of nanomaterials on crop growth and metal and metalloid uptake, before finally testing a flexible quantitative approach, known as the IVIF-TOPSIS-EW method, that can illuminate how to choose different types of nanomaterials according to a range of realistic agricultural scenarios.

The results show that nanomaterials are more effective than conventional fertilizers at mitigating the harmful effects of polluted soil (by 38.3%), can enhance crop yields (by 22.8%) and the nutritional value of those crops (by 30%), as well as combat plant stress (by 21.6%) due to metal and metalloid pollution. Nanomaterials also help increase soil enzymes and organic carbon, both of which help drive soil fertility.

“Of course, nanomaterials are not a silver bullet,” explains Xing. “They need to be applied in distinct ways based on the individual crop and soil.”

This is where the team’s IVIF-TOPSIS-EW method comes into play.

“Our method can help policy makers choose the best course of action for their particular situation,” says Ma.