Researchers from the Laboratory for Theory and Simulation of Materials at EPFL in Lausanne, part of the NCCR MARVEL, have used computational methods to identify what could be the thinnest possible metallic wire, as well as several other unidimensional materials with properties that could prove interesting for many applications.

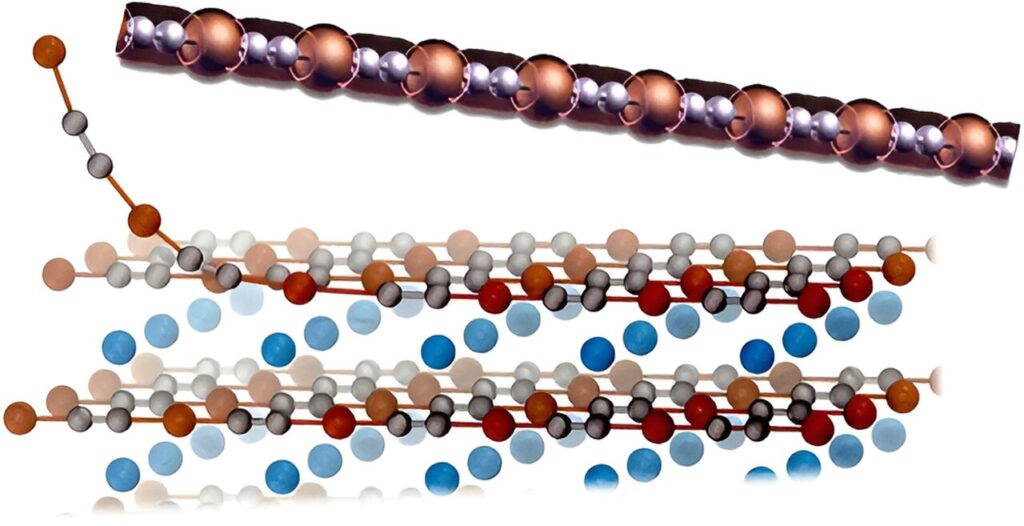

Unidimensional (or 1-D) materials are one of the most intriguing products of nanotechnology and are made of atoms aligned in the form of wires or tubes. Their electrical, magnetic, and optical properties make them excellent candidates for applications ranging from microelectronics to biosensors to catalysis.

While carbon nanotubes are the materials that have received most of the attention so far, they have proved very difficult to manufacture and control, so scientists are eager to find other compounds that could be used to create nanowires and nanotubes with equally interesting properties, but easier to handle.

So, Chiara Cignarella, Davide Campi and Nicola Marzari thought to use computer simulations to parse known three-dimensional crystals, looking for those that—based on their structural and electronic properties—look like they could be easily “exfoliated,” essentially peeling away from them a stable 1-D structure. The same method has been successfully used in the past to study 2D materials, but this is the first application to their 1-D counterparts.

The researchers started from a collection of over 780,000 crystals, taken from various databases found in the literature and held together by van der Waals forces, the sort of weak interactions that happen when atoms are close enough for their electrons to overlap. Then they applied an algorithm that considered the spatial organization of their atoms looking for the ones that incorporated wire-like structures, and calculated how much energy would be necessary to separate that 1-D structure from the rest of the crystal.

“We were looking specifically for metallic wires, which are supposed to be difficult to find because 1-D metals, in principle, should not be sufficiently stable to allow for exfoliation,” says Cignarella, who is the first author of the paper.

In the end, they came up with a list of 800 1-D materials, out of which they selected the 14 best candidates—compounds that have not been synthesized as actual wires yet, but that simulations suggest as feasible. They then proceeded to compute their properties in greater detail, to verify how stable they would be and what electronic behavior one should expect of them.

Four materials—two metals and two semi-metals—stood out as the most interesting ones. Among them is the metallic wire CuC2, a straight-line chain composed by two carbon atoms and one copper atom, the thinnest metallic nanowire stable at 0 K found so far.

“It’s really interesting because you would not expect an actual wire of atoms along a single line to be stable in the metallic phase,” says Cignarella. The scientists found that it could be exfoliated from three different parent crystals, all known from experiments (NaCuC2, KCuC2 and RbCuC2). It requires little energy to be extracted from them, and its chain can be bended while preserving its metallic properties, which would make it interesting for flexible electronics.

Other interesting materials found in the study, which is published in ACS Nano, include the semi-metal Sb2Te2, which because of its properties, may allow for studying an exotic state of matter predicted 50 years ago but never observed, called excitonic insulators, one of those rare cases where quantum phenomena become visible at the macroscopic scale. Then there are Ag2Se2, another semi-metal, and TaSe3, a well-known compound that is the only one to have already been exfoliated in experiments as a nanowire, and that the scientists used as a benchmark.

As for the future, Cignarella explains that the group wants to team with experimentalists to actually synthesize the materials, while continuing computational studies to see how they transport electric charges and how they behave at different temperatures. Both things will be fundamental to understanding how they would perform in real-world applications.

Provided by

National Centre of Competence in Research (NCCR) MARVEL