A drug-carrying molecule designed to cure disease by slipping past the lung’s natural defenses offers new hope for people with chronic or deadly respiratory diseases, say its creators, researchers in assistant professor Liheng Cai’s Soft Biomatter Lab at the University of Virginia School of Engineering and Applied Science.

Cai and his team, including materials science and engineering Ph.D. student Baiqiang Huang and biomedical engineering Ph.D. student Zhi-Jian He, successfully demonstrated the nanocarrier’s effectiveness using the lab’s own “micro-human airway.” The device captures the geometric and biological features of human airways.

They describe their findings in a paper published in the journal ACS Nano.

Sneaking past our defenses

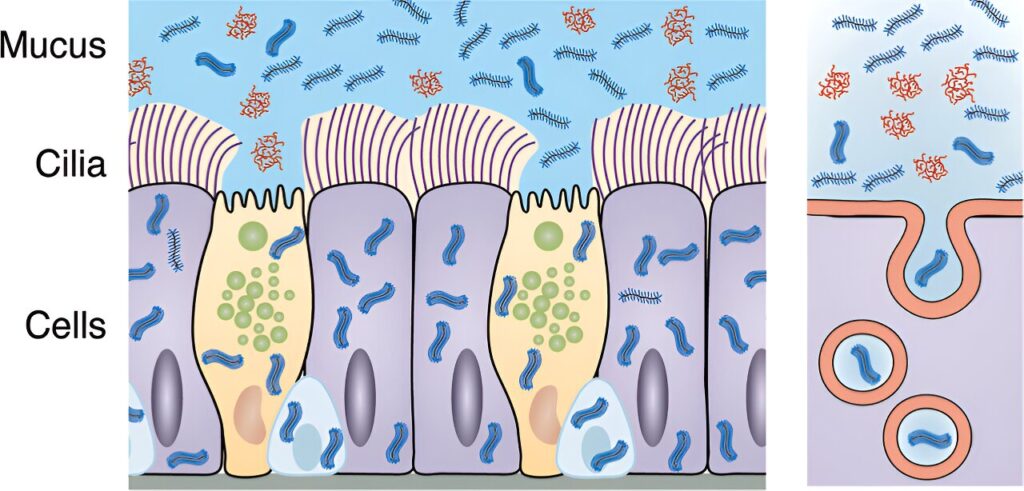

Our lungs have layers of protection that trap and transport pathogens or inhaled particles out of the respiratory system to prevent us from getting sick. Every time you blow your nose, the system is working.

“Unfortunately, those same barriers also stop medicine from reaching targeted cells, making it hard to treat diseases such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and pulmonary fibrosis,” Huang said.

The new polymer is called bottlebrush polyethylene glycol, or PEG-BB. It moves quickly through the airway battlements by mimicking mucins, a natural glycoprotein responsible for the properties of mucus, which has the same bottlebrush shape—a central backbone with a thicket of bristles extending outward.

“We thought the flexibility and wormlike geometry of the bottlebrush carrier would let it sneak through the tight mesh of mucus and gels surrounding the cilia to be internalized by epithelial cells, where the drugs are needed to work,” Huang said.

Cilia are the hairlike structures on the surface of cells. They move in conjunction with mucus to repel and expel foreign bodies.

To test their hypothesis, the team cultured human airway epithelial cells in their device. They introduced fluorescent PEG-BB molecules into the cells from two directions.

They then used a dye to penetrate the mucus and periciliary layers—the latter being the gel engulfing the cilia. They did not dye the epithelial cell walls, which helped mark the epithelium’s boundaries.

Using a specialized microscope and darkened room to sharpen the images, they were able to see how well the glowing bottlebrush molecules had moved through the cells.

A string of recent successes

“The micro-human airway is basically an equivalent home for the cells to grow,” Huang said.

“Its biological similarities let us study human lung defense, without causing harm to living beings,” added Cai, whose lab specializes in developing novel bottlebrush polymers for an array of uses, many of them pushing boundaries in precision medicine.

For instance, his bioprinting program recently produced what could be the first 3D building block for printing organs on demand.

The PEG-BB findings represent one more in the lab’s string of successes.

“We think this innovation not only promises better treatments of lung diseases with reduced side effects, but also opens possibilities for treating conditions affecting mucosal surfaces throughout the body,” Cai said.

The lab’s next step is to test PEG-BB’s ability to carry drug molecules across a mucus barrier. The team is experimenting with both in vitro and in vivo models in mice.